Amarie's Story

It was New Year’s Eve. Kiara Crawford, then 21, had a mission and a menu: Toasting the New Year with a festive dinner of beef tacos and chicken enchiladas and a glass of sparkling cider. Kiara’s contractions had started the week prior, but that evening they got really bad really fast, leaving her doubled over in pain. Her mom, Michelle Dallas, asked if she needed to go to the hospital.

“I’m fine. We can make tacos. We’re going to do this,” Kiara insisted, until her mother overruled her and they sped to the closest hospital. At 4:46 a.m. on Jan. 1, Kiara’s daughter, Amarie Rose, was born preterm, much earlier than her expected delivery date on March 19. Amarie weighed just 2 pounds, 10 ounces. The tiny infant was whisked to Children’s National Hospital, known for its diverse array of specialists skilled in caring for preemies like Amarie.

At 4:46 a.m. on Jan. 1, Kiara’s daughter, Amarie Rose, was born preterm, much earlier than her expected delivery date on March 19. Amarie weighed just 2 pounds, 10 ounces. The tiny infant was whisked to Children’s National Hospital, known for its diverse array of specialists skilled in caring for preemies like Amarie.

Kiara remained at the delivery hospital, forlorn. She had imagined how her first childbirth would play out. She expected to carry the baby to full term. She expected to leave the hospital with her newborn, just like everyone else.

“I didn’t even get a chance to hold her,” she recalls. “I didn’t even know what she looked like.”

The 24 hours it took to be reunited with her newborn and to hold her for the first time felt like an eternity. “I think I cried. I was so─I don’t know the word─amazed that we could make something so special. Then, I felt a little sad. I couldn’t take her home. Everybody else got to leave with their baby.”

In the weeks that Amarie remained in the Children’s National Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), Kiara kept to a clockwork schedule, visiting the NICU daily to bond with her baby.

“I think she knew who I was. She would look at me for a little bit. I think we started to establish a routine. I tried to come at the same time every day; she knew I was coming,” she recalls.

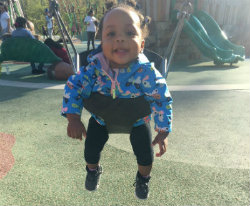

During that time, she was told about a clinical research study looking at premature infants like Amarie and how preterm birth impacts their developing brains. Every month, Kiara celebrates Amarie’s rapid growth as she gains weight, grows taller and masters new skills: maintaining eye contact, latching onto a finger with an iron grip, holding her head up, sitting up, crawling, standing, babbling, developing her own unique personality.

At the completion of the five-year observational study, parents and researchers hope to learn more about the subtle differences in how the brain develops in babies born early, like Amarie, compared with neurodevelopment seen in babies who were delivered after full-term pregnancy.

Specifically, the research team wants to know about differences in the cerebellum─the brain region responsible for processing information streaming in from other parts of the brain in order to make smooth, coordinated movements and to maintain balance─in preterm infants compared with babies born full term.

“We know from previous studies that the cerebellum develops very rapidly in the third trimester of pregnancy. The growth rate is so rapid, it outpaces growth that occurs in any other structure of the brain during that time frame,” says Catherine Limperopoulos, PhD, principal investigator of Project ONESIE. “Our goal is to identify ways to best support this vulnerable brain region throughout this critical development period to ensure that babies have the best possible outcomes in school and in life.”

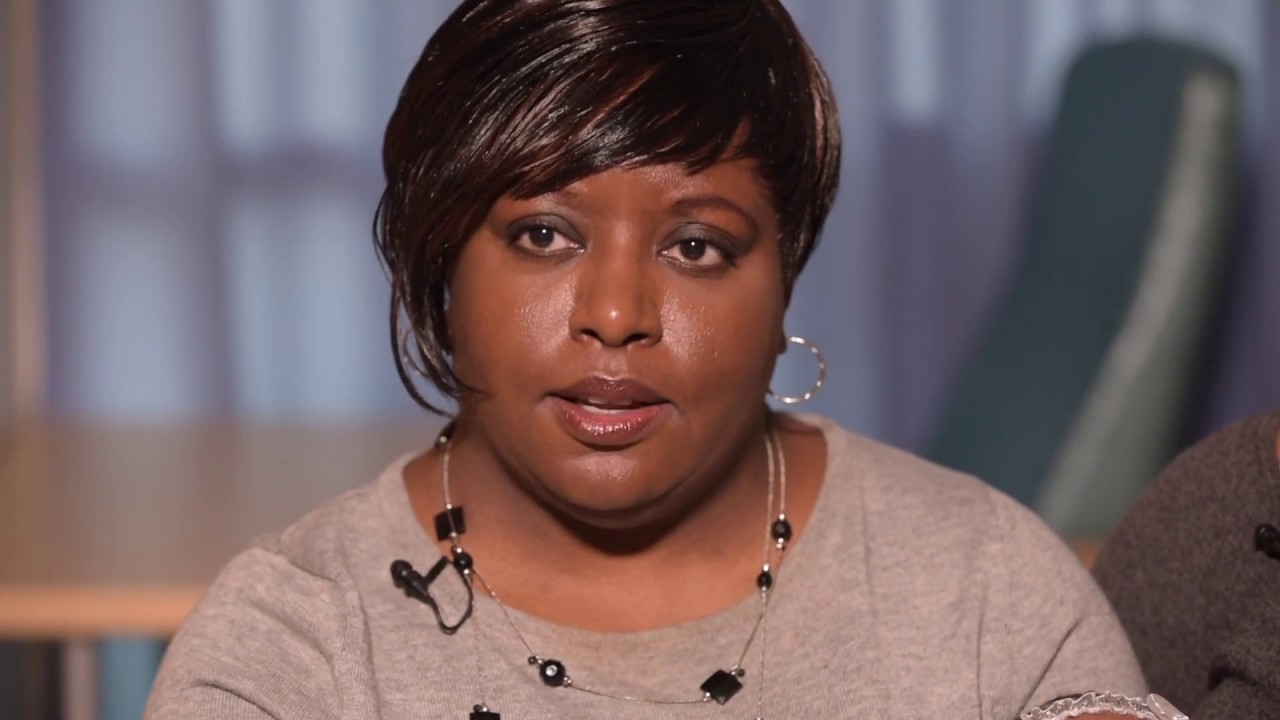

Michelle is now grandmother to an infant born preterm and mother to a preemie daughter─Kiara’s sister─who weighed only 3 pounds, 13 ounces when she was born 15 years ago.

Michelle is now grandmother to an infant born preterm and mother to a preemie daughter─Kiara’s sister─who weighed only 3 pounds, 13 ounces when she was born 15 years ago.

“If we can be a blessing to someone else, we should,” Michelle says. The family was especially excited about their ability to participate in a research study that aims to answer questions raised by both preterm births.

“I want to know if there is that much of a difference. I know there is a difference in physical size. Cognitively, is there any difference?” Kiara adds. “I feel like Amarie started out really small. But she can catch up with kids born around her age. Just because they’re born preemies doesn’t mean they can’t learn like everyone else. Just because they’re born preemies doesn’t mean they can’t do all the things they’re supposed to do at their age.”

Amarie's Care Team Departments

Care Team

This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate, or jump to a slide with the slide dots.

Project ONESIE: Protecting the vulnerable preterm cerebellum

Kiara Crawford and her mother, Michelle Dallas, explain why they enrolled Amarie in a research study at Children’s National that seeks to understand how preterm birth affects the cerebellum, a brain region responsible for motor coordination and that also may play a role in attention and language.

Be the Reason a Child Smiles

Every day at Children’s National Hospital, lives are changed through compassionate care and groundbreaking discoveries. Your charitable donation helps us deliver expert treatment and hope to thousands of children and families.

Meet the patients whose stories inspire us—and see the difference your support makes.